Either because I am sliding into senescence or because I have a fondness for ink on the page, I routinely print my e-mails, read them, and then sacrifice them to the wastebasket or the fireplace.

Such was not the fate of the communication below, which for the last five years has survived in breast pockets, hatbands, and, for several months in the Congo, my left boot. It has been my constant companion, but now we must part.

What follow are Ivy Lambert’s last words.

Montag

* * *

Dear Montag,

Just time for a quick note before I finish packing. All that’s left is my sketch pad and pencil bag, but I think I’ll put those in my carry-on. Don’t want to risk losing them if my checked luggage gets lost between here and Vienna. THANK YOU for suggesting the trip! I still can’t believe I’m leaving in just a few hours.

Thank you also for the DVD. The cover and the tagline, not to mention the title*, led me to believe the movie would be some sort of prehistoric potboiler, but it was nothing like that at all. So glad you didn’t ruin it for me by telling me what to expect.

I love this movie! You know my half-baked theories about how art got started–well, evidently so did the filmmakers. I don’t think I’ve ever seen or read anywhere else about the possibility that the first ever artist was a woman. But it makes so much sense, doesn’t it? So cool that they kind of lead you down the wrong track in the first scene when the tribe is walking down the mountains to the river valley for the winter. At first I thought the baby being carried on the mother’s back was a boy–or at least not a girl. Anyway, how did they know my trick of closing my eyes to fix an image of what I’m looking at and sketching it in my mind? I’ve told you about that, right? They did that beautifully when they showed the baby blinking after looking up at some clouds. At first you think the baby is just trying to get the sun out of its eyes, but when they show the clouds looking like a horse or a cave bear, and then they show the outlines of those same clouds taking shape on a black screen, I knew immediately that they were showing the inside of the baby’s eyelids, her personal movie theater.

One of the things that’s so great is that this film shows what the first artist may have been like, from the moment she was born. I don’t remember making a conscious decision to draw, I just did it. It was who I was from the earliest time I could remember. They show it as a natural progression of how she interacts with the world around her. She just can’t help wanting to record it somehow. It’s who she is.

Oh, also, so you know the scene where the young girl is sitting on a rock and looking at a herd of horses in the distance, and the character played by a young (and very handsome) Werner Herzog approaches her from behind and we don’t know that her eyes are closed? That was brilliant. She was tracing in the air the image she was seeing in her head. And then Werner’s reaction when he realizes there’s something very strange about this girl. He can’t decide whether he likes it or not. It’s funny because we all know Werner likes strange.

I almost couldn’t believe the scene when the girl, who’s a young woman by this time, makes what may be the most profound discovery in the history of humanity by figuring out how to turn those tracings in the air into marks on a wall–and it’s an accident!

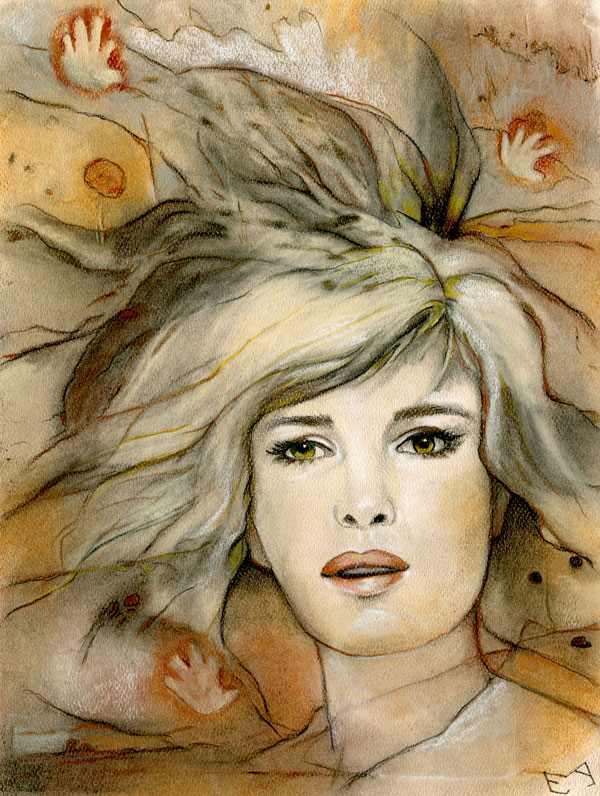

I swear the director must have had a direct line into my brain, because that moment is exactly how I’ve always imagined it. Monica Vitti runs her hands over the dead aurochs that the male members of the tribe have killed and brought into the cave. She doesn’t want to help her old mother and all the other women skin it and gut it. She’s more interested in remembering it by touching it, getting the feel of the creature under her hands. And then she retreats to her little cave-nook (the first studio!), and we see she’s been collecting things–bones, twigs, flowers and plants that she’s dried, pretty rocks. She makes a fire and her shadow flickers on the cave wall behind her. The sound of water dripping from the ceiling is a metronome, counting down the beats to this moment. She reaches out to the stream to wash the aurochs’ blood from her hands, but then she stops. She looks at her hand. She looks down at her lap. A drop of blood falls onto her garment. She watches as it soaks in. And then–it hits her! She takes her finger and spreads the blood around–she makes a mark! She looks at that mark and then closes her eyes.

I think I stopped breathing at that point in the film. But when she reached out her hand to touch the cave wall, and drew the outline of the aurochs on it, I just exploded, and so did the score (I think I jumped out of my chair). But, she doesn’t realize that Werner has been watching her from a hidden alcove, and when he sees what she’s done (his reaction such a powerful mix of fear and awe) he knows that the world has been changed forever, and that he must possess this magical creature.

Which of course, he does. And then the title becomes a double entendre. Still, I prefer to think that the hands of fire belonged to the artist. They were blood-red after all. A point we can debate, I suppose.

Don’t you love the montage where Vitti experiments with different materials to make her cave paintings? Blood, pollen, dirt added to water, burnt ends of twigs, ashes from the fire. Then using the animal bones to grind the elements into pigments, and using the clay on the cave floor to make little figurines. I know they compressed thousands of years into a few minutes, but I thought it was lovely.

I can’t decide whether the ending was happy or sad. Ultimately happy, I suppose. But what a great direction for the movie to take to show Vitti having a baby of her own, and then teaching her how to be an artist. And then showing other children the same thing, passing down what she knows. Ooh, and that bit about the clay figures being toys for the children–brilliant!

I could barely watch when the other members of the clan discovered where their children have been disappearing to, and they don’t understand. I can’t bear to think about that scene, but of course throughout the ages, what man fears, he must destroy. But then Vitti, on her dying breath, takes a small clay figurine of a woman out of her smock (right? She has to have a smock!) and gives it to her daughter. The daughter cradles it, caresses it, and closes her eyes. Ralph Vaughan Williams’ plaintive final strains play as the screen fades to black.

And I cry my heart out.

Well. I must bid you adieu, Montag. My plane awaits. I think my first stop in Vienna will be the Naturhistorisches. Love to Gert and to Nelson! I can’t wait to share my sketches with everyone.

XOXO,

Ivy

*Mani di fuoco